Toi Derricotte’s “Another poem of small grieving for my fish Telly”

Another poem of small grieving for my fish Telly

Perhaps I should forgive

Telly for dying in my care, Just a

fish, someone said, Just

get another. Lucille said

our power becomes

greater when we lose the flesh; so,

when I poured Telly out

of his painted casket (a little wooden

egg) out over the rail

into the all

becoming, was it a miracle

that he had lived, was it a miracle?

Once, when I prayed for a sign,

God opened the closed

vault of the sky, the sun popped out

& shone directly in my face, & hail, yes,

hail started falling (in July). I was

afraid to believe in love. God,

don’t waste your miracles on me. &

the sun went back, like a face

retreating. Telly, you are bodi-

less, you are with my mother

& father. Say it wasn’t my

fault you suffered, with your little

working gills, say you forgive me.

Whenever I teach line and line break I turn to Toi Dericotte, and her collection The Undertaker’s Daughter. I met Toi first at Cave Canem in 2014. When I returned in 2016 I thought she wouldn’t remember me; there are so many CC fellows, how could she? But when she saw me in the dining hall she looked at me and held me with such love in her eyes, it reminded me of those adoring looks my grandma gives. It made no sense that she could look at me like that when we knew each other so little. But love flows from Toi, you can feel it easily in her presence and in her work.

Some of my favorite poems of hers that ooze with this tenderness are the ones to her fish Telly. As a baby poet I wouldn’t have dared to write about a dog, let alone a fish. To me, those were the type of silly poems white poets got to write because their world wasn’t under threat. But Toi taught me otherwise: that tenderness is as much my birthright, even if the world is determined to tell me otherwise.

Not only is Toi’s work a study on tenderness, but it is a model on the importance of the poetic line and line break, and the flexibility of language. When I read this poem, “Another poem of a small grieving for my fish Telly,” with my students, I remind them that we are to read both at the level of the sentence but also at the level of the line, so that we can hear the way Toi makes use of all the echoes or meanings behind a word or phrase.

From the very first line “Perhaps I should forgive” Toi gestures openly by breaking the line at forgiveness. So that, if you’ve read the rest of her book you can’t help but think she must be talking about her difficult father. Even reading the poem out of context, the line break leaves an openness that allows you to linger in the idea of forgiveness and the hesitancy of that “Perhaps” that starts the line. As a result, the reader enters the poem through the tension of forgiveness and recognizes that even if we are talking about “just/a fish” this will be a big poem.

Further, by repeatedly placing the “just” at the end of the line she emphasizes the word so that we hear the callousness of it. Just a tiny lesser being the speaker of those words seems to say just a tiny portion of your heart.

In the heart of this writer there is no “just.” Instead Toi instructs us that it is human to give the heart, not in portion, but wholly—even to something as tiny as a beta fish. Writing “when I poured Telly out/of his painted casked (a little wooden/egg) out over the rail/into the all/becoming, was it a miracle/ that he had lived, was it a miracle?” She asks us to stop and consider the destiny of the soul of this tiny being. My two favorite lines there are “into the all” and “becoming, was it a miracle.” When read at the level of the sentence the phrase is “into the all becoming,” which on its own feels like an appropriate description for the afterlife. However, by breaking it up, Toi allows us to sit in that “all” and, perhaps in doing so, shows us the connection between the soul of a fish and the soul of the human who cared for it. Some day we all, tiny or large being, will enter that all. Then in addition to the weighty expansiveness of that “all” we get the interesting question in the next line “becoming, was it a miracle,” which allows us to think about this conundrum of the soul more deeply. Isn’t it a miracle that we “become,” that we enter into existence at all?

Of course, being a poet, Toi leaves us with the question and leaps. In a line that sits alone at the center of a poem like a hinge, she begins the story of a time she prayed for a sign, and “God opened the closed.” This section of the poem has an ecstatic momentum to it that’s accentuated by the choices Toi makes when breaking her lines. For example, by breaking the line at “& hail, yes,” after describing the sky opening so the sun can shine directly on her face, Toi helps us hear an ecstatic “hell yes!” in that “hail, yes,” even without Toi directly putting those words in the poem. The ear can’t help but hear it and the line break accentuates that hearing.

Similarly, in the next stanza Toi manipulates the line in such a way that the meaning of the sentence is once again deliberately undermined or expanded. She writes “…I was/afraid to believe in love. God,/don’t waste your miracles on me. &/….” First by putting “God” at the end of the second line of that stanza the line becomes “afraid to believe in love. God” making it sound to the ear and eye that Toi is afraid to believe in both God and love. Or perhaps is afraid to believe more specifically in the “love God,” a fear which resonates with the physical and emotional violence we see in other portions of the book. Yet in the next line she writes “don’t waste your miracles on me. &” When I read these lines to my students I always point out that there was no reason that Toi had to put “God” at the end of the second line and “&” at the end of the third, except that she wanted us to push beyond the level of the sentence. And so that abrupt “&” at the end of “don’t waste your miracles on me,” quite immediately undermines the statement. It's as if she’s saying “don’t waste your miracles on me EXCEPT maybe do.” And I must say theres a vulnerability here that is so particular to Toi’s work. By undercutting these two sentences with her breaks, Toi shows a hesitation, an uneasiness with declaring a belief in love or God, a desire to throw off miracles and a desire for them. Theres a very human uncertainty that these choices bring out that is deeply relatable.

I used to rush to the end of this poem because of my excitement for the the final stanza “& father. Say it wasn’t my/fault you suffered…say you forgive me.” Here was the true heart breaking moment in the poem where the fish is revealed to be merely a vehicle for what I felt the poem must really be about: seeking forgiveness from the father, and that pervasive feeling of guilt that makes a child feel that they are the cause of their parents suffering. And to keep it for real, I still don’t think it's an accident that the final stanza starts “& father.” But I’ve come to realize, especially after re-reading this poem in the context of the other Telly poems, that to say the fish is only a vehicle would be a betrayal of the expansiveness of the heart of this poet. The fish leads to the father, not because of artifice or a false poetic craftiness, but because love leads you to love, and grief to grief. Of course the dead mother and father enter this poem about the dead fish because as she says in a later Telly poem:

“all things are

connected, a

circle,

bread on the water, as my mother said,

always comes home.”

(from “Because I was good to Telly in his life,")

John Allen Taylor’s “After All”

After All

I call my father to tell him about a poem

I’ve written, just published somewhere

he might see. It’s about ________, I say.

It’s not about ________. He says he loves me.

He says You know every now and then

I’ll cast a crown that sits poorly and rocks

on its post—so I recast it.

My father is a dentist.

What he means is if I worked harder

I could write happy poems.

He says he loves

the poem I wrote for my mother.

He says It shines. He doesn’t say that.

He says he likes how he feels

when he reads it. He means Can you write

about me like that?

John Allen Taylor’s “After All,” is an unveiling of all the ways it can be difficult to write honestly about our families, particularly our parents. “After All,” was published in John’s chapbook titled Unmonstrous which was published by YesYes books last spring. John and I met in gradschool in Boston though we are both from the same suburban areas of California. His grandfather lived in the same neighborhood I grew up in, almost exactly behind my house I think. One day, before I had come out to my family, John came to pick me up from home over the Christmas holiday. It was probably the first or second time we had seen each other in California, and certainly one of very few if any times my father has seen me hug a man who is not in my family. After John had left, my dad made the joke that fathers of daughters make about guns and protecting their “babygirls.” I wasn’t pleased with my dad’s reflex towards violence and made that clear. I tried too, perhaps with marginal success, to explain that a brother mustn’t always look like one. Sometimes its enough to simply share the same compassions the same desire for a generous and kind spirit.

You can feel this poet’s gentle compassion for his own father in his poem “After All,” which tells the story of a phone call the speaker has with his father after publishing a poem somewhere the father “might see.” In a poem as narrative as “After All,” what is said on the page becomes increasingly as important as what isn’t. With that in mind, by emphasizing merely the possibility of the father’s gaze we are able to read for its significance to the speaker. While this paternal gaze is not a place of fear, it is certainly not a place of comfort either, if for no other reason than the fact that parents like young children can feel like wells of never ending questions if given too much access to their adult children’s personal life. Even in the poets refusal to name the actual subject of the poem discussed “...Its about _______, I say/Its not about _______. He says I love you,” We hear both, what is present and absent in this father son dynamic. How love, or at least the profession of it, is and is not enough.

Yet and still, even in this poem about lack there is a wealth of compassion for all that the speaker’s father can and cannot give in the moment of this conversation. John starts the next stanza with italics from the speaker’s father and then offers us a translation:

“He says You know every now and then

I’ll cast a crown that sits poorly and rocks

on its post—so I recast it.

My father is a dentist.

What he means is if I worked harder

I could write happy poems”

In order to begin the translation of the speaker’s father, John offers us a simple fact, his occupation, a dentist. Again we are meant to read for what is unsaid, and imagine the distance between how a poet and dentist might see the world and communicate. We are, also, meant to let go of our desire to read the father’s speech as metaphor and to read it over again literally as the father meant it, then again metaphorically as poets must inevitably hear it. We are meant to translate for the poet too, to hear the absurdity of the idea that happy poems are something that can be “worked harder” at. However, in his refusal to impose the poet’s ear or rather the poet’s shout of frustration over what the father says John leaves us room to hear the father, however briefly, without judgement.

In the stanza that follows, the translation between father and son begins to happen more seamlessly, beginning with the enjambment of the opening line which leaves the reader even more space to wonder what and how the father loves. John writes

“ He says he loves

the poem I wrote for my mother.

He says It shines. He doesn’t say that.

He says he likes how he feels

when he reads it. He means Can you write

about me like that”

The introduction of the mother at the very end of the poem and the tension between how the speaker writes for her and how he writes about everything else (the father included) brings us to the heart of the poem, the risk. Here we realize the commonality between the father and son, the desire to be seen and and held beneath a loving gaze. In the acknowledgement of that commonality, that desire to have something made for us that “shines” that “feels” good when read, we are able to see again, how after it all our parents are just like us, just like young children wanting to see and feel love, asking incessantly look at me look at me, “Can you write/about me like that.” All the while not knowing what exactly they are asking of us. John’s poem “After All” reminds us first that we all only want to be seen and seen through kinder eyes, and second that even in our kindness even in our desire to give and receive compassion there is always room for the truth we may yet struggle to speak aloud.

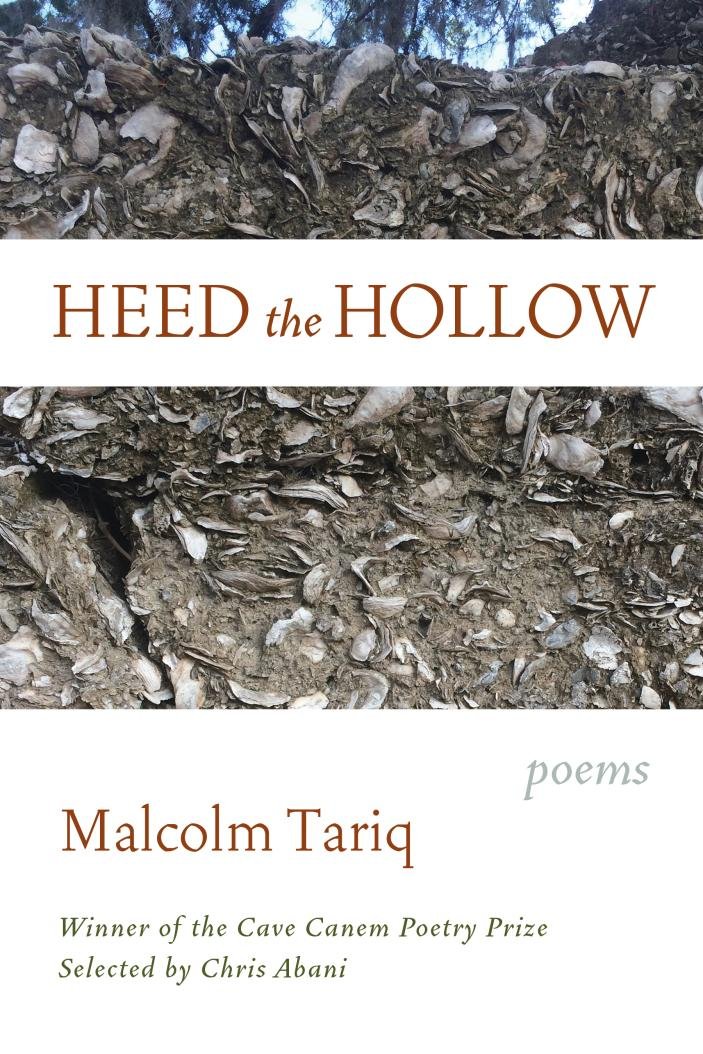

Malcolm Tariq's "Callie Barr's Black Bottom"

From Heed the Hollow by Malcolm Tariq

You may find her behind

Rowan Oak, a shadow

of fortress where then now

you find no real entry place.

Where then now a tree grows

near that door, purple flower

heads peeking through into

the world she left behind.

Here then now she found a home

as shadow, covering

it all with her big black

small frame of big womanness

now then where the cabin creaks.

You may find somewhere

her portrait stuck to a wall

where then now she lingers,

shadows peeking over her face

to find the proclaimed Mammy

joy. They leave themselves to

tell her story, to guess her

age unknown and rounded out.

Here then now she lies absent,

erased by the very word—

entry marked into the bottom

of history where then now

we find no shadow of life

as told by her. History carries

her tale through his and her mouth.

Say: I heard it like this

now then where she lingers

on tongues that spit out the bad

taste to tell a good story.

Say: Here lies Mammy, born

in bondage, died in devotion

and love. Where then now

they opened earth’s

mouth ready to receive her

body. Stretched that back

over her. Placed the tombstone

as muzzle that says: “Mammy.

Her white children bless her,”

where then now her black children

listened and watched that doing,

going back into their shadows

after she lay buried in the maid’s

uniform as they say she requested.

Then now there was it

emblem of her service or her life?

Where then now is Callie?

Malcolm Tariq’s “Callie Barrs Black Bottom,” is a reclamation of Black history’s often externally imposed silences. This poem comes from Malcolms first collection of poetry Heed the Hollow. At the launch of Malcolm’s book last November one of the audience members quite appropriately described Heed the Hollow “as an “Epistemology of the Bottom.” Perhaps what is beautifully genius and joyful about this epistemology is Malcolm’s willingness to go for all of the meanings and contexts of the word “bottom:” bottom as buttocks, base, mule, as sexual partner, as place. Only a poet who is comfortable with both language’s coy expansiveness and its silences can write such an important and beautiful study.

Like any poet with at least a passing knowledge of U.S. history Malcolm knows that you cannot do a study of the bottom without acknowledging Black women’s place there. We have been, as Zora Neal Hurston, said the “mules of the world,” and so you cannot talk about the history of the bottom without talking about Black women. “Callie Barr’s Black Bottom” addresses the concept of the bottom as a physical historical place. The flexibility of its meaning within this poem is echoed in the words “where then now” which are repeated with some variation like a refrain. What is most heart rending about this poem is its ability to address the way that history is often placed like a “tombstone as muzzle over” Black women’s lives.

At his book launch Malcolm spoke about being influenced by Jean Toomer when he was writing this book. And it made me think about Alice Walkers description of Jean Toomer’s work at the start of her essay “In Search of Our mothers Gardens”

“When the poet Jean Toomer walked through the South in the early twenties, he discovered a curious thing: black women whose spirituality was so intense, so deep, so unconscious, that they were themselves unaware of the richness they held. They stumbled blindly through their lives: creatures so abused and mutilated in body, so dimmed and confused by pain, that they considered themselves unworthy even of hope.”

Like Jean Toomer Malcom knows that when you study Black women you study a history of both deep pain and deep beauty. However, unlike Jean Toomer, Malcolm’s poem, in acknowledging that “we find no shadow of life/ as told by her,” leaves space for Black women’s knowledge of ourselves and the bottom where we reside and have resided for centuries, even if that knowledge often goes unheard.

Probably the best way to talk about all that’s going on underneath the surface of “Callie Bars Black Bottom,” is to start by unpacking the wealth of allusion in Malcom’s poem. All that is said or hinted at without being said in the poem. We’ve already talked some about the title, but perhaps one of the successes of this poem is that you don’t need to know who Callie Barr is to enjoy it. That said once you do a quick google search and learn that Callie Barr was William Faulkner’s mammy the ways that she has been completely and utterly silenced by history become all the more devastating. The narrative of the poem starts by leading the reader to Callie Barr’s home, her “Black Bottom,” a reference also to the Bottom in Toni Morrison’s novel Sula, which for Callie lies behind Rowan Oak, William Faulkner’s home.

For the first eight lines, the poet contrasts the images of the two homes turning Callie Barr’s very real home into a metaphysical conceit for the poem. To that end Callie Barr and her home are described in constant shadow her home is “a shadow/ of fortress where then now/ you find no real entry place,” she is described later as having “found a home/ as shadow, covering” even “her portrait stuck to a wall/where then now she lingers,” has “shadows peek[]over her face/ to find proclaimed Mammy/ joy...” Finally by the end of her poem even her own Black children are described as “going back into their shadows/ after she lay buried in the maid’s/uniform as they say she requested.” The muzzling of life in the shadows is probably best described in its first iteration where the poet writes “you find no real entry place,” because there really is no entry into a shadow. No way to reach back and ask of them their history. Shadows after all are simply places the light couldn’t reach because something larger or perhaps simply more obtuse was standing in the way.

Let’s talk briefly about the unnamed obtuse in this poem. The Faulkners, who had the audacity to place on Callie Barr’s headstone only the words “Mammy./Her white children bless her.” Please someone, tell me how William Faulkner is supposed to be both one of the great American novelist, which I can concede he is, and also too ridiculously obtuse to see the complete an utter erasure in those lines. That we are willing to call him great and also willing to forgive him for refusing to use Callie Barr’s name on her own headstone, says everything you will ever need to know about American history. America says: “Well what was he denying her by calling her Mammy.” We who know better say: “Everything.”

Fortunately, as I said before, this poem “Callie Barr’s Black Bottom” is a reclamation, and Malcolm Tariq in first refusing to name the Faulkner’s in this poem and in second calling out their foolishness is reclaiming this bottom so that America can acknowledge it for the place of white thievery that it is. Malcolm acknowledges this thievery by calling out the theft of Callie Barr’s voice and stories. William Faulkner based several of his Mammy characters on Callie Barr and even dedicated one of his novels to her, because of how much he was influenced by her stories as a child and adult writer. The poem shows this by describing how “[The Faulkners] leave themselves to tell her story,” how “History carries/ her tale through his and her mouth.” Essentially how the great story teller William Faulkner like many a great man before and after him stole his magic sauce from the Black woman who raised him. What kills me most are the italics imagining things the Faulkner’s may have said about Callie Barr “Here lies Mammy, born/ in bondage, died in devotion/and love.” We may never know how Callie Barr really felt about the people who employed her through the second half of her life. We can only know the world in which she sought that employment, and know how few if any other options were afforded to her. We can only know that love, or at least, the appearance of love was necessary for her survival, and if it thats the case we know nothing else but that whatever she felt for those people, who buried her in her maids uniform, couldn’t’ve been love.

“Where then now is Callie?” the poet asks we echo him deeply.

Camille Rankine "Necessity Defense of Institutional Memory"

NECESSITY DEFENSE OF INSTITUTIONAL MEMORY

So the free may remain free

say the nightmare

the dream

so we are preserved

he who believes takes a life

so a life may be saved

the girl becomes an object

so the greatest devastation occurs

let go her fingers their slim cleave

so I may be replaced

by a machine which in its violence behaves

more like me

the longer you live the more these lies

come alive

so the past splits in two:

one stays in the past and dies

one past shape-shifts walks with you

Honestly y’all, I was going to skip this week because I’m supposed to be packing, but every time I open my phone to do a lil downtime scrolling I keep getting confronted with the ever rising chaotic violence of this moment. There’s the federal agents kidnapping protesters in Portland, and forcing them to sign documents saying they will no longer protest in order to be released. There’s the Black celebrity trying to turn “coon” into some snappy acronym, really Terry? Theres Naked Athena and this baffling proclamation that a “western vagina” will save us all?! I am still waiting for an explanation of what the hell a “western vagina” is by the way.

As you might imagine, that low hum of dread that’s been buzzing since quarantine started was getting really really loud, but fortunately I was saved by this quote from James Baldwin that the poet Joy Priest posted on twitter.

“The poets, by which I mean all artist, are finally the only people who know the truth about us. Soldiers don’t. Statesmen don’t. Priests don’t. Union leaders don’t. Only the poets...It sounds mystical, I think, in a country like ours and at a time like this, but something awful is happening to a civilization when it ceases to produce poets, and what’s is even more crucial, when it ceases in anyway whatever to believe in the report that only poets can make.” (“The Artists Struggle for Integrity,” 1963.)

Fortunately, we have not stopped producing poets, and so I thought, let me get back to this work and see what the poets have to report about this moment we’re in, because somebodies got to make it make sense. And by “make it make sense” I mean someone’s got to put all this into social historical and emotional context for me, because if I tell you one of the things that I struggle with as I watch the discourse of this moment is how ahistorical and narrow minded we can be as a culture. I swear folks be out here putting on blinders like those race horses, and be acting like, well all I see is this moment right here right now and I shan’t look at all the other back story and surrounding information. And like thats fine if you’re a Black girl at home trying to enjoy watching the Bennet sisters find they husbands without wondering about the probability of Mr. Darcy also owning a plantation in one of them British colonies in addition to half of Darbyshire, but it does not work for our current political moment. In fact, its high key how we got here in the first place.

I could rant for days about this mess, but I’d rather talk about Camille Rankine’s poem, “Necessity Defense of Institutional Memory.” I came across this poem while reading Camille’s first book Incorrect Merciful Impulses. Returning to it this morning I realized a lot of my frustrations with our discourse is really my frustration with our institutional memory. A frustration this poet validates through her subtle exploration of the dangers of institutional memory and the belief in its necessity. When I approach the opening to this poem one of the things I’m most struck by is what is not said. Camille puts so much trust in us as readers right from start, “So the free may remain free,” she writes trusting us to hear what is sublimated underneath so the oppressed remain oppressed or to ask but who are the free.

Very quickly this poem asks us to choose how or where we locate ourselves within it. Are you among the free and the “we” that gets preserved? And what does it mean to be outside of that freedom and preservation? The unspoken duality in those lines is fleshed out in the couplet between them “say the nightmare is/ the dream.” Here we see the tension between the two realities, between the American Dream and the violence and cruelty perpetuated on the people who try as they might are never meant to attain it. The line break in that couplet is wonderful, “say the nightmare is” she writes, allowing that sublimated voice to insist on their reality, that it not be erased, that it not say be turned into another story of say the antebellum south with those happy slaves that loved their oppressors.

The form of the poem on the page further emphasizes this duality between dream and nightmare. The lines swaying back and forth across with that alternating indentation work as a sort of call and response or cause and effect. So “this” can happen “this” happens or is sacrificed. And so we see the danger of the preservation in the effect it has or in the violence that is necessary to maintain it. “He who believes takes a life.” And again in the couplet that follows there’s the reality of those who live the dream, a life saved, and the reality of those who live the nightmare, the girls inevitable objectification. Yet that boundary between dream and nightmare seems to collapse in the lines that follow.

so a life may be saved

the girl becomes an object

so the greatest devastation occurs

let go her finger their slim cleave

The realties of violence begins to appear in the left column of the poem, starting with that “greatest devastation,” where before there had only been freedom and preservation and safety. It makes me think of something I read about the federal abductions in Portland being the natural evolution of ICE abducting immigrants while they were at work or going to pick up their children from school or at school themselves. All of which started well before Trump I might add. What they’ll do to the most vulnerable among us they’ll do to any of us. As is often the case all of our preservation and freedom and safety is only an illusion if we are not fighting to protect and defend everyone.

By the time we reach the center of this poem we are all made complicit in the violence of institutional memory. Where we might have been left space to negotiate our relation to the “we,” “he,” and “girl” earlier in the poem, with the shift to the imperative in the line beginnns “let go her fingers” we are held quite firmly in place. We, the readers, are the ones releasing the girls fingers, failing to protect her to keep her reality from becoming a nightmare. And my lord how we are convicted by the word choice that follows the caesura “their slim cleave.” The particularity of slim fingers giving us the image of a young child’s hands, and then that word cleave doing so much work as meaning both to cling and separate. Taken all together we can imagine this child clinging to us even as we separate from her to live out the dream and make our selves mute to the reality of her nightmare.

Finally, the end of this poem, that very heroic feeling couplet, says so much about where we are now. The past feels so much at once alive and dead, doesn’t it? We are constantly denying and reliving our history. Fascism is taking over, we are marching for Black lives, people are being abducted, people are being murdered in broad daylight on camera, people are being lynched. We are idolizing the Wall of Moms joining the protest for Black lives as if Black mothers haven’t been at the center of this movement from its inception, as if we haven’t been watching them for years on camera begging the police to stop killing their babies. It’s hard not to have an eery sense of déjà vu.

I often leave this poem wondering how much we are bound to this shape-shifting undead past that walks on with us. I’m not sure we can ever escape it, but if its possible, if there’s a world where we can see the past without the rhetoric and revisionism that allows it to shape-shift, erase and perpetuate violence in the present, then I think poetry and art is the way we’ll learn.

Camille Rankine is the daughter of Jamaican immigrants. Her first full-length collection of poetry, Incorrect Merciful Impulses, was published in 2016 by Copper Canyon Press. She is also the author of the chapbook Slow Dance with Trip Wire, selected by Cornelius Eady for the Poetry Society of America's 2010 New York Chapbook Fellowship. The recipient of a 2010 "Discovery"/Boston Review Poetry Prize, she was featured as an emerging poet in the April 2011 issue of O, The Oprah Magazine and as one of Brooklyn Magazine’s top 100 cultural influencers of 2017. Her poetry has appeared in numerous journals, including The Baffler, Boston Review, Denver Quarterly, Narrative, Octopus Magazine, A Public Space, The New York Times and Tin House. She is the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and The MacDowell Colony, and was named an Honorary Cave Canem fellow in 2012. A graduate of Harvard University and Columbia University's School of the Arts, she chairs the Board of Trustees of The Poetry Project, and co-chairs the Brooklyn Book Festival Poetry Committee. She is a visiting professor of creative writing at The New School and lives in New York City.