Malcolm Tariq's "Callie Barr's Black Bottom"

From Heed the Hollow by Malcolm Tariq

You may find her behind

Rowan Oak, a shadow

of fortress where then now

you find no real entry place.

Where then now a tree grows

near that door, purple flower

heads peeking through into

the world she left behind.

Here then now she found a home

as shadow, covering

it all with her big black

small frame of big womanness

now then where the cabin creaks.

You may find somewhere

her portrait stuck to a wall

where then now she lingers,

shadows peeking over her face

to find the proclaimed Mammy

joy. They leave themselves to

tell her story, to guess her

age unknown and rounded out.

Here then now she lies absent,

erased by the very word—

entry marked into the bottom

of history where then now

we find no shadow of life

as told by her. History carries

her tale through his and her mouth.

Say: I heard it like this

now then where she lingers

on tongues that spit out the bad

taste to tell a good story.

Say: Here lies Mammy, born

in bondage, died in devotion

and love. Where then now

they opened earth’s

mouth ready to receive her

body. Stretched that back

over her. Placed the tombstone

as muzzle that says: “Mammy.

Her white children bless her,”

where then now her black children

listened and watched that doing,

going back into their shadows

after she lay buried in the maid’s

uniform as they say she requested.

Then now there was it

emblem of her service or her life?

Where then now is Callie?

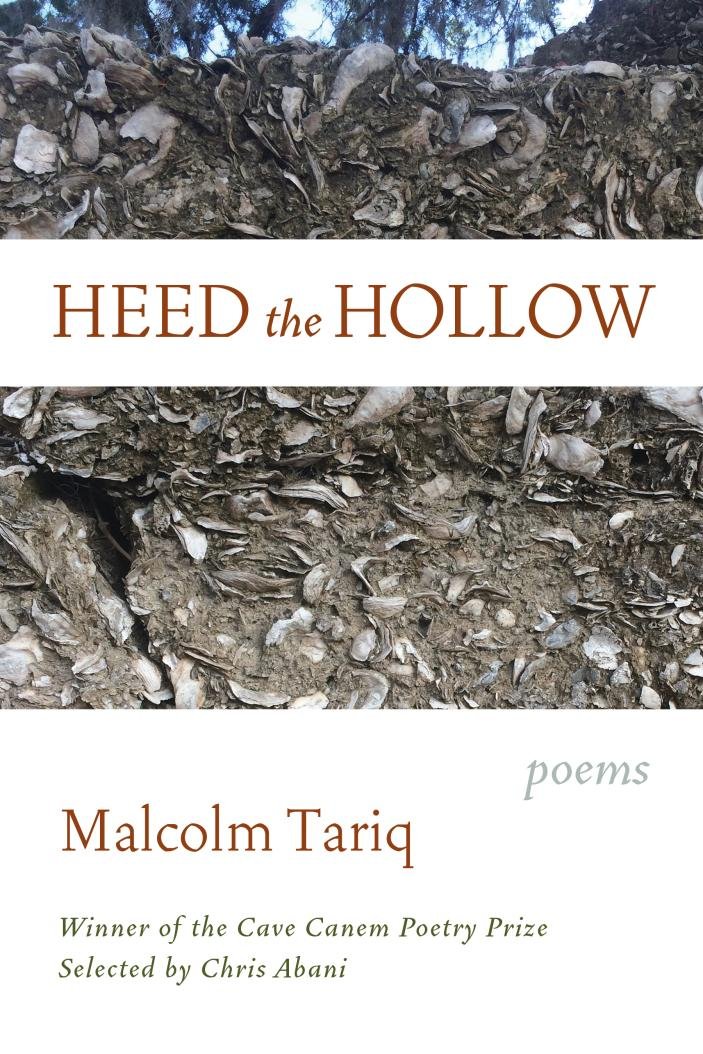

Malcolm Tariq’s “Callie Barrs Black Bottom,” is a reclamation of Black history’s often externally imposed silences. This poem comes from Malcolms first collection of poetry Heed the Hollow. At the launch of Malcolm’s book last November one of the audience members quite appropriately described Heed the Hollow “as an “Epistemology of the Bottom.” Perhaps what is beautifully genius and joyful about this epistemology is Malcolm’s willingness to go for all of the meanings and contexts of the word “bottom:” bottom as buttocks, base, mule, as sexual partner, as place. Only a poet who is comfortable with both language’s coy expansiveness and its silences can write such an important and beautiful study.

Like any poet with at least a passing knowledge of U.S. history Malcolm knows that you cannot do a study of the bottom without acknowledging Black women’s place there. We have been, as Zora Neal Hurston, said the “mules of the world,” and so you cannot talk about the history of the bottom without talking about Black women. “Callie Barr’s Black Bottom” addresses the concept of the bottom as a physical historical place. The flexibility of its meaning within this poem is echoed in the words “where then now” which are repeated with some variation like a refrain. What is most heart rending about this poem is its ability to address the way that history is often placed like a “tombstone as muzzle over” Black women’s lives.

At his book launch Malcolm spoke about being influenced by Jean Toomer when he was writing this book. And it made me think about Alice Walkers description of Jean Toomer’s work at the start of her essay “In Search of Our mothers Gardens”

“When the poet Jean Toomer walked through the South in the early twenties, he discovered a curious thing: black women whose spirituality was so intense, so deep, so unconscious, that they were themselves unaware of the richness they held. They stumbled blindly through their lives: creatures so abused and mutilated in body, so dimmed and confused by pain, that they considered themselves unworthy even of hope.”

Like Jean Toomer Malcom knows that when you study Black women you study a history of both deep pain and deep beauty. However, unlike Jean Toomer, Malcolm’s poem, in acknowledging that “we find no shadow of life/ as told by her,” leaves space for Black women’s knowledge of ourselves and the bottom where we reside and have resided for centuries, even if that knowledge often goes unheard.

Probably the best way to talk about all that’s going on underneath the surface of “Callie Bars Black Bottom,” is to start by unpacking the wealth of allusion in Malcom’s poem. All that is said or hinted at without being said in the poem. We’ve already talked some about the title, but perhaps one of the successes of this poem is that you don’t need to know who Callie Barr is to enjoy it. That said once you do a quick google search and learn that Callie Barr was William Faulkner’s mammy the ways that she has been completely and utterly silenced by history become all the more devastating. The narrative of the poem starts by leading the reader to Callie Barr’s home, her “Black Bottom,” a reference also to the Bottom in Toni Morrison’s novel Sula, which for Callie lies behind Rowan Oak, William Faulkner’s home.

For the first eight lines, the poet contrasts the images of the two homes turning Callie Barr’s very real home into a metaphysical conceit for the poem. To that end Callie Barr and her home are described in constant shadow her home is “a shadow/ of fortress where then now/ you find no real entry place,” she is described later as having “found a home/ as shadow, covering” even “her portrait stuck to a wall/where then now she lingers,” has “shadows peek[]over her face/ to find proclaimed Mammy/ joy...” Finally by the end of her poem even her own Black children are described as “going back into their shadows/ after she lay buried in the maid’s/uniform as they say she requested.” The muzzling of life in the shadows is probably best described in its first iteration where the poet writes “you find no real entry place,” because there really is no entry into a shadow. No way to reach back and ask of them their history. Shadows after all are simply places the light couldn’t reach because something larger or perhaps simply more obtuse was standing in the way.

Let’s talk briefly about the unnamed obtuse in this poem. The Faulkners, who had the audacity to place on Callie Barr’s headstone only the words “Mammy./Her white children bless her.” Please someone, tell me how William Faulkner is supposed to be both one of the great American novelist, which I can concede he is, and also too ridiculously obtuse to see the complete an utter erasure in those lines. That we are willing to call him great and also willing to forgive him for refusing to use Callie Barr’s name on her own headstone, says everything you will ever need to know about American history. America says: “Well what was he denying her by calling her Mammy.” We who know better say: “Everything.”

Fortunately, as I said before, this poem “Callie Barr’s Black Bottom” is a reclamation, and Malcolm Tariq in first refusing to name the Faulkner’s in this poem and in second calling out their foolishness is reclaiming this bottom so that America can acknowledge it for the place of white thievery that it is. Malcolm acknowledges this thievery by calling out the theft of Callie Barr’s voice and stories. William Faulkner based several of his Mammy characters on Callie Barr and even dedicated one of his novels to her, because of how much he was influenced by her stories as a child and adult writer. The poem shows this by describing how “[The Faulkners] leave themselves to tell her story,” how “History carries/ her tale through his and her mouth.” Essentially how the great story teller William Faulkner like many a great man before and after him stole his magic sauce from the Black woman who raised him. What kills me most are the italics imagining things the Faulkner’s may have said about Callie Barr “Here lies Mammy, born/ in bondage, died in devotion/and love.” We may never know how Callie Barr really felt about the people who employed her through the second half of her life. We can only know the world in which she sought that employment, and know how few if any other options were afforded to her. We can only know that love, or at least, the appearance of love was necessary for her survival, and if it thats the case we know nothing else but that whatever she felt for those people, who buried her in her maids uniform, couldn’t’ve been love.

“Where then now is Callie?” the poet asks we echo him deeply.