John Allen Taylor’s “After All”

After All

I call my father to tell him about a poem

I’ve written, just published somewhere

he might see. It’s about ________, I say.

It’s not about ________. He says he loves me.

He says You know every now and then

I’ll cast a crown that sits poorly and rocks

on its post—so I recast it.

My father is a dentist.

What he means is if I worked harder

I could write happy poems.

He says he loves

the poem I wrote for my mother.

He says It shines. He doesn’t say that.

He says he likes how he feels

when he reads it. He means Can you write

about me like that?

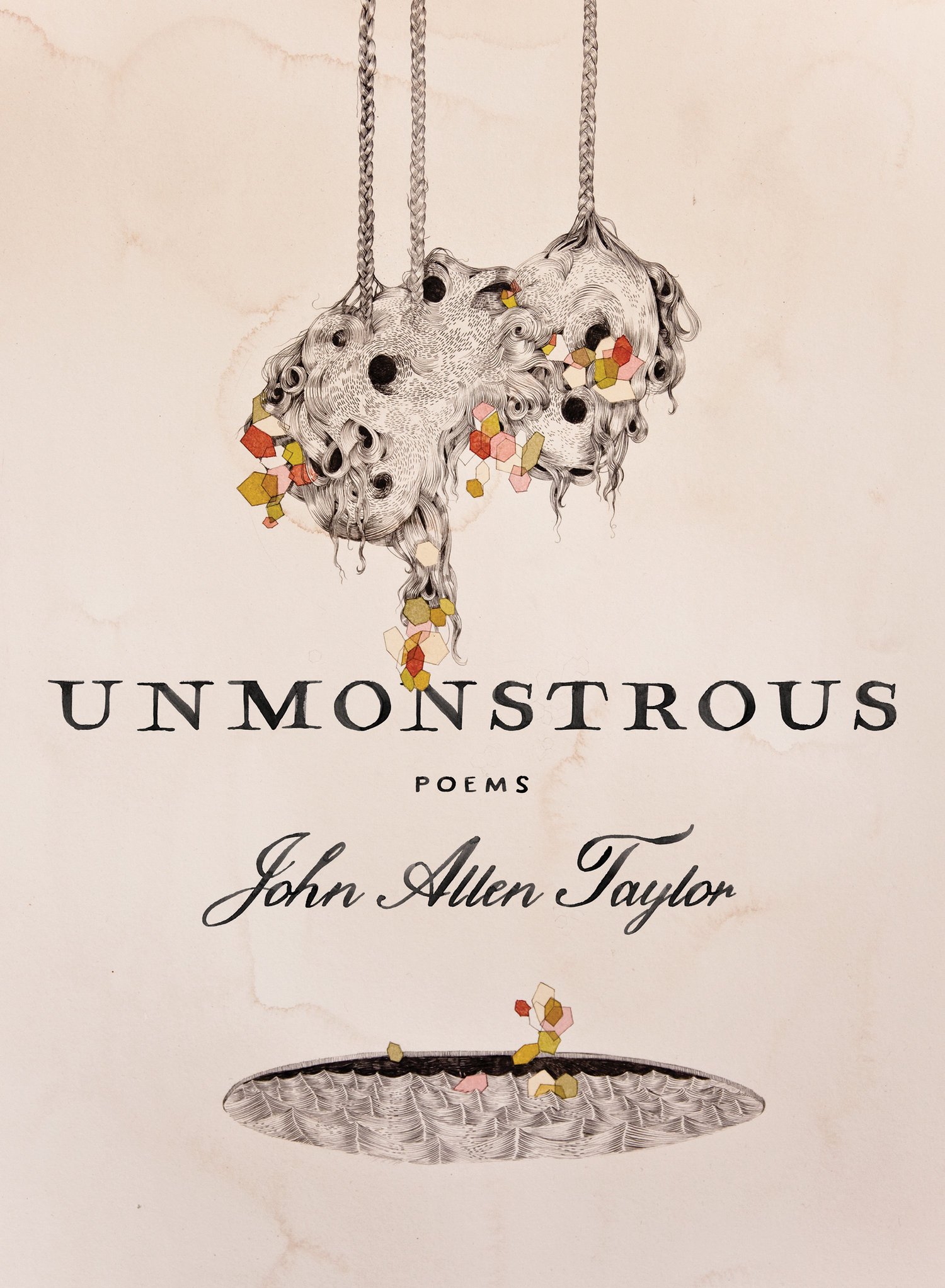

John Allen Taylor’s “After All,” is an unveiling of all the ways it can be difficult to write honestly about our families, particularly our parents. “After All,” was published in John’s chapbook titled Unmonstrous which was published by YesYes books last spring. John and I met in gradschool in Boston though we are both from the same suburban areas of California. His grandfather lived in the same neighborhood I grew up in, almost exactly behind my house I think. One day, before I had come out to my family, John came to pick me up from home over the Christmas holiday. It was probably the first or second time we had seen each other in California, and certainly one of very few if any times my father has seen me hug a man who is not in my family. After John had left, my dad made the joke that fathers of daughters make about guns and protecting their “babygirls.” I wasn’t pleased with my dad’s reflex towards violence and made that clear. I tried too, perhaps with marginal success, to explain that a brother mustn’t always look like one. Sometimes its enough to simply share the same compassions the same desire for a generous and kind spirit.

You can feel this poet’s gentle compassion for his own father in his poem “After All,” which tells the story of a phone call the speaker has with his father after publishing a poem somewhere the father “might see.” In a poem as narrative as “After All,” what is said on the page becomes increasingly as important as what isn’t. With that in mind, by emphasizing merely the possibility of the father’s gaze we are able to read for its significance to the speaker. While this paternal gaze is not a place of fear, it is certainly not a place of comfort either, if for no other reason than the fact that parents like young children can feel like wells of never ending questions if given too much access to their adult children’s personal life. Even in the poets refusal to name the actual subject of the poem discussed “...Its about _______, I say/Its not about _______. He says I love you,” We hear both, what is present and absent in this father son dynamic. How love, or at least the profession of it, is and is not enough.

Yet and still, even in this poem about lack there is a wealth of compassion for all that the speaker’s father can and cannot give in the moment of this conversation. John starts the next stanza with italics from the speaker’s father and then offers us a translation:

“He says You know every now and then

I’ll cast a crown that sits poorly and rocks

on its post—so I recast it.

My father is a dentist.

What he means is if I worked harder

I could write happy poems”

In order to begin the translation of the speaker’s father, John offers us a simple fact, his occupation, a dentist. Again we are meant to read for what is unsaid, and imagine the distance between how a poet and dentist might see the world and communicate. We are, also, meant to let go of our desire to read the father’s speech as metaphor and to read it over again literally as the father meant it, then again metaphorically as poets must inevitably hear it. We are meant to translate for the poet too, to hear the absurdity of the idea that happy poems are something that can be “worked harder” at. However, in his refusal to impose the poet’s ear or rather the poet’s shout of frustration over what the father says John leaves us room to hear the father, however briefly, without judgement.

In the stanza that follows, the translation between father and son begins to happen more seamlessly, beginning with the enjambment of the opening line which leaves the reader even more space to wonder what and how the father loves. John writes

“ He says he loves

the poem I wrote for my mother.

He says It shines. He doesn’t say that.

He says he likes how he feels

when he reads it. He means Can you write

about me like that”

The introduction of the mother at the very end of the poem and the tension between how the speaker writes for her and how he writes about everything else (the father included) brings us to the heart of the poem, the risk. Here we realize the commonality between the father and son, the desire to be seen and and held beneath a loving gaze. In the acknowledgement of that commonality, that desire to have something made for us that “shines” that “feels” good when read, we are able to see again, how after it all our parents are just like us, just like young children wanting to see and feel love, asking incessantly look at me look at me, “Can you write/about me like that.” All the while not knowing what exactly they are asking of us. John’s poem “After All” reminds us first that we all only want to be seen and seen through kinder eyes, and second that even in our kindness even in our desire to give and receive compassion there is always room for the truth we may yet struggle to speak aloud.