Nicole Sealey "In Defense of Candelabra with Heads"

IN DEFENSE OF “CANDELABRA WITH HEADS”

If you’ve read the “Candelabra with Heads”

that appears in this collection and the one

in The Animal, thank you. The original,

the one included here, is an example, I’m told,

of a poem that can speak for itself, but loses

faith in its ability to do so by ending with a thesis

question. Yeats said a poem should click shut

like a well-made box. I don’t disagree.

I ask, “Who can see this and not see lynchings?”

not because I don’t trust you, dear reader,

or my own abilities. I ask because the imagination

would have us believe, much like faith, faith

the original “Candelabra” lacks, in things unseen.

You should know that human limbs burn

like branches and branches like human limbs.

Only after man began hanging man from trees

then setting him on fire, which would jump

from limb to branch like a bastard species

of bird, did we come to know such things.

A hundred years from now, October 9, 2116,

8:18 p.m., when all but the lucky are good

and dead, may someone happen upon the question

in question. May that lucky someone be black

and so far removed from the verb lynch that she be

dumbfounded by its meaning. May she then

call up Hirschhorn’s Candelabra with Heads.

May her imagination, not her memory, run wild.

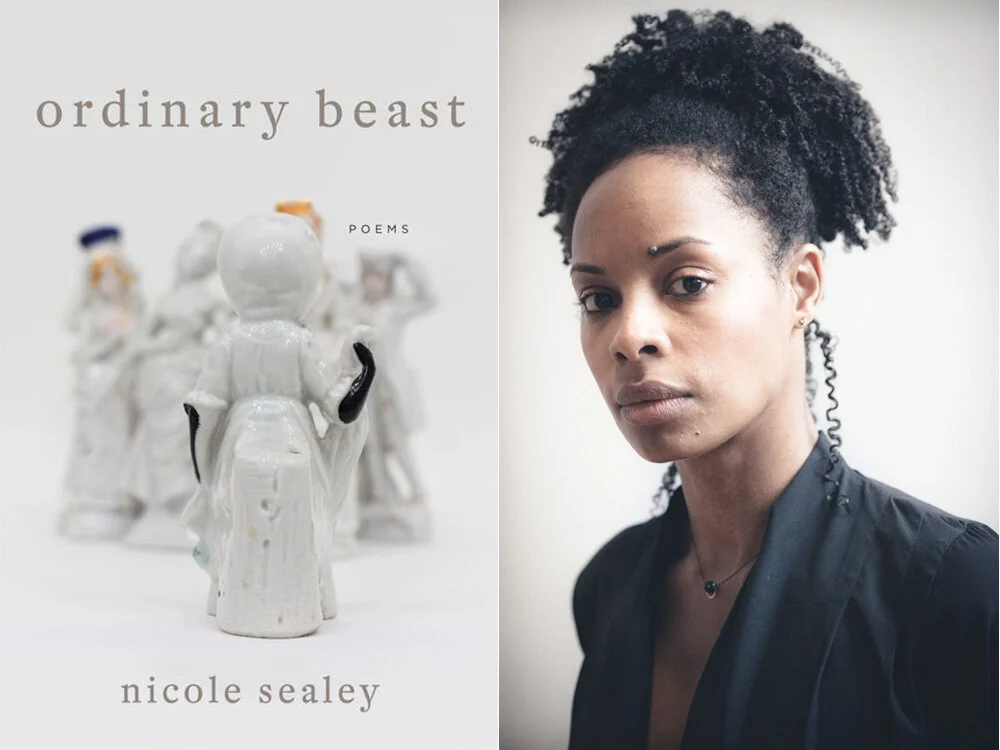

Every time I’ve heard Nicole Sealey, author of the chapbook The Animal After Whom Other Animals are Named, and the full length collection Ordinary Beast, read the poem “In Defense of ‘Candelabra with Heads’” I have wanted to press rewind and hear it again. This was particularly true the first time I heard Nicole read this poem at Mass Poetry festival in 2018. That particualar reading took place in a lecture hall at some large museum in Salem, Massachuesettes, and like anything Massachuesettes puts on the audience was predominantly white, which is, if I’m honest, the reason I left Boston though I really did love it as much as I’ve loved any city I’ve lived in. In most scenarios I really do hate to be the only or one of very few little brown dots in a sea of whiteness. After the 2016 election, when I had been invited to read to a very generous if tipsy crowd of well meaning white people, who all proceeded to apologize to me personally for dtrumps election as the single representative of colored peoples present. I decided to no longer allow myself to be alone among white people I didn’t know and alcohol, which is honestly a good way to operate while Black in America. Yet, despite all my qualms about being alone in white spaces, on this day when I shuffled in among the masses to hear the then Executive Director of Cave Canem read from her first book, and heard the last line of this poem “May her imagination, not her memory, run wild.” I knew I had been in the right room at the right time. I knew I had been blessed.

“In Defense of Candelabra with Heads,” begins so conversationally that unless you are deeply familiar with the original poem it defends, which is also by Nicole, you have no idea that a blessing is coming or from where. “In Defense” begins with a description of the original “Candelabra with Heads” which is an ekphrastic poem or a poem about a piece of art and takes its title from the sculpture it is responding to, which was created by the artist Thomas Hirschorn. The poem compares the sculpture to images of lynchings. When the poem “Candelabra with Heads” was originally published in Nicole’s chapbook the editors convinced her that the thesis statement “Who can see this and not see lynchings?” was unnecessary. This poem explains why it is.

The defense of the original poem begins with a reference to a line from William Yeats “a poem should click shut/like a well made box.” However, rather than describing the way the thesis of “Candelabra with Heads” “click[s the poem] shut” she describes instead how it clicks open by inviting us into the realm of the Black imaginary.

“I ask, ‘Who can see this and not see lynching?’

not because I don’t trust you, dear reader,

or my own abilities. I ask because the imagination

would have us believe, much like faith, faith

the original “Candelabra” lacks in things unseen.”

First, I must say I love the way we are addressed as “dear readers” here and how it maintains the intimacy established earlier in the poem with that “thank you” for having read the poem as it appears in both books. This intimacy is important, because the poet is asking us to trust her. She is saying it is safe to dream, to have faith, to leave room for what “the imagination would have us believe,” though history may make mockery of our faith.

It feels important too to note that we are speaking in this poem of a faith “the original Candelabra lacks in things unseen.” A faith that was edited out at the advice of well meaning editors who perhaps didn’t appreciate the scope of the poets vision for her poem. A faith the poet nevertheless nurtured and maintained and defended for us publicly, offering, by example, a reminder to trust ourselves, and our vision for our work. (ok let me hop off my soap box and get back to the poem)

The faith, the imagination, the hope this poem invites us to have is not blind to reality. After all Nicole is quick to remind us how we learned “that human limbs burn/like branches and branches like human limbs.” Her description of lynch fire “which would jump/from limb to branch like a bastard species/of bird” echoes the peculiarity of Billie Holidays “Strange Fruit,” the metaphors in both texts showing how human cruelty can make perversions of nature.

Yet even despite the long bitter history of violence against Black people Nicole is able to create a speculative world “A hundred years from now...when all but the lucky are good/and dead” where Black Americans are finally free from this trauma. She writes,

“...may someone happen upon the question

in question. May that lucky someone be black

and so far removed from the verb lynch that she be

dumbfounded by its meaning. May she then

call up Hirschorn’s Candelabra with Heads

May her imagination, not her memory, run wild.”

Notice how, with this shift into the speculative, the poets language shifts too, and becomes in some ways incantatory. May this may this may this the poet says calling forth a world that does not yet exists, as if through magic. Every time I have heard the end of this poem read aloud, even when I am just home alone reading to myself, I cannot help but “get happy” as the old folks would say and if I am home alone I cannot help but lift my hands in praise in recognition of this poet’s power. She has imagined a world where Black girls and women like me might live more freely, where we might bring with us our minds and not be bound by what history tells us is true, but by whatever world we might dare to make for ourselves. That is a blessing I can receive, and echo with a resounding and enthusiastic Amen.

Nicole Sealey is the author of Ordinary Beast (Ecco Press, 2017), which was a finalist for the PEN Open Book and Hurston/Wright Legacy Awards. Her chapbook, The Animal After Whom Other Animals are Named (Northwestern University Press, 2016), was the winner of the 2016 Drinking Gourd Chapbook Prize.

Rage Hezekiah "Honing"

https://www.ragehezekiah.com/

Since so many of us are at home alone missing the deliciousness of touch, and because nothing is quite so exquisite and radical as an exploration of queer Black femme pleasure, and because our pleasures is so precious so invaluable. I thought I’d start with this stunner by my good friend Rage Hezekiah.

HONING

Sprawled open, my v-wide thighs

held the faucet hostage

awaiting the eruption I’d found

while filling myself,

bringing water deep

into my own brimmed vessel

beneath lips vast enough

to hold a fist, no—

a body newly mine

I gave myself to this, a bath

and time alone to bloom,

submerged in bubbles

my budded nipples piercing

the steam-filled room. Tight

breath muffled under

thunderous rushing, the water—

thrummed relentless

in the best way until

I spilled over, sinking

bicuspids into my bicep

blossoming/breaking

into affirmation: yes this

a new kind of wholeness

both/and

yes

The last time I heard this poem read aloud was among family. Not my own family, thank god, but the poet’s, Rage Hezekiah author of the full length collection of poems Stray Harbor and the chapbook Unslakable. There was a long delay after Rage read the poem’s final words, which end with an emphatic and ecstatic yes. Some of the family were still squirming in the joy filled awkwardness of what we had witnessed; of all the autoerotic sex the poem so freely celebrates. We were all old enough to know what the “yes” and the “yes this” that preceded it were referring to. How in a more performative reading those words might rightly be gasped, but still we chose to sit in our awkwardness pretending, as families will sometimes, that we didn’t recognize ourselves in the image of the speaker taking her pleasure beneath the bathtubs gushing faucet. I, at least, tried to smile at what I knew was a good poem. A poem that deserved to be celebrated. I wasn’t the only one who felt this way. Moments into our awkward silence, as if experiencing a delay, one of the poet’s aunts exclaimed “You are so cool,” loud enough so that we all giggled in the back cafe of the book store where we poets had been shuffled aside to do our reading; our pleasure and tension released out into the room with the auntie’s exclamation. This poem and this poet are to quote her aunt “cool.”

What is cool about this poem, and more importantly, what is beautiful about much of Rage’s work is its use of music. In this poem which is so deeply and exquisitely about sensual pleasure, and not just pleasure but the pleasure of people assigned female at birth. Rage carries the reader from pleasure to pleasure to crescendo by way of the carefully crafted musicality of her language. From the beginning the poem uses open vowel sounds like the aw and oh sounds in the first two lines “sprawled open, my v-wide thighs/held the faucet hostage,” which invites the reader, when speaking this poem aloud, to open their mouths wider, like those “v-wide thighs,”in the opening lines, and to, by extension open themselves to pleasure as they enter further into the poem.

“Honing” continues its musicality through its middling point which reads:

“I gave myself to this, a bath

and time alone to bloom,

submerging in bubbles

my budded nipples piercing

the steam filled room. Tight”

Here, the poem continues a chorus of “B” sounds which has been bubbling up through the poem from “bringing” to “brimmed” to “beneath and “body” down into four of the five lines quoted above. These bubbling “B’s”, when given attention, feels almost like a rumbling up or crescendo toward the orgasm the reader can, by now, at least hope to read at the end of the poem. It should be noted that the poet in some ways ends this crescendo of “B”’s before the orgasm with the screaming “ee” sounds in “piercing” which is enjambed or rather placed intentionally on the end of the line. That loud “ee” at the end of a line after the soft sounds of “bath” bloom” and bubbles” feels almost like an audible extension of the speakers pleasure and not just the bodies response to it.

The imagery in “Honing” is just as gorgeous as the sound because of how fully it captures the bodies experience of pleasure in the moment of seeking and encountering orgasm. For example, look at the poets use of water here.

“breath muffled under

thunderous rushing, the water—

thrummed relentless

in the best way until

I spilled over, sinking”

Here the movement of water begins to act as a metaphor for the build of pleasure in the body. It is “thunderous” and “thrumm[ing] relentlessly,” these lines are effective because they can be read both literally as the water of the faucet falling with gusto. Or and more importantly they can be read as metaphor for the orgasm that “spills over” in the speaker by the end draining them so completely that she seems almost to lose her buoyancy by the end of it and as the enjambment of the line suggest start “sinking.”

The final lines of the poem move away from strict imagery into the poems gentle thesis. An edit or re-envisioning of its title “honing” which is a word often used to describe the sharpening of a knife. Rage’s use of “Honing” though allows for a less phallic more femme centered read of the word. While the poem does end with a single word or point on a line “yes” we are meant, I think, to read this “yes” as holding in it not a single exclamation but everything that comes before. “Yes” then, is a word for “both/and” it is a word of opening of both “blossoming” and “breaking” it can’t contain only a single feeling, as no word can, and so must contain all of them and in doing so creates something new. A “wholeness” that is as inclusive as it is expansive. A “yes” I think we can all echo and loudly. “Yes” we say. “yes this.”

Rage Hezekiah is a New England based poet and educator, who earned her MFA from Emerson College. She has received fellowships from Cave Canem, The MacDowell Colony, and The Ragdale Foundation, and is the recipient of the Saint Botolph Foundation's Emerging Artists Award. Her poems have been anthologized, co-translated, and published internationally. Find out more and support this poet by checking out her website here.

What am I doing here?

This space will celebrate the poems and poets who have filled me up and carried me from day to day—poems that feel like sanctuary, like a place to say amen, a place to be seen and understood, a place to know that what you are feeling has been felt before, poems that say there is a language and a home for you.