Toi Derricotte’s “Another poem of small grieving for my fish Telly”

Another poem of small grieving for my fish Telly

Perhaps I should forgive

Telly for dying in my care, Just a

fish, someone said, Just

get another. Lucille said

our power becomes

greater when we lose the flesh; so,

when I poured Telly out

of his painted casket (a little wooden

egg) out over the rail

into the all

becoming, was it a miracle

that he had lived, was it a miracle?

Once, when I prayed for a sign,

God opened the closed

vault of the sky, the sun popped out

& shone directly in my face, & hail, yes,

hail started falling (in July). I was

afraid to believe in love. God,

don’t waste your miracles on me. &

the sun went back, like a face

retreating. Telly, you are bodi-

less, you are with my mother

& father. Say it wasn’t my

fault you suffered, with your little

working gills, say you forgive me.

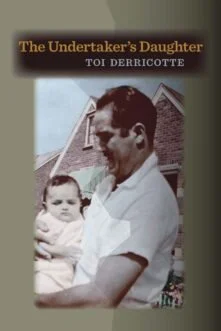

Whenever I teach line and line break I turn to Toi Dericotte, and her collection The Undertaker’s Daughter. I met Toi first at Cave Canem in 2014. When I returned in 2016 I thought she wouldn’t remember me; there are so many CC fellows, how could she? But when she saw me in the dining hall she looked at me and held me with such love in her eyes, it reminded me of those adoring looks my grandma gives. It made no sense that she could look at me like that when we knew each other so little. But love flows from Toi, you can feel it easily in her presence and in her work.

Some of my favorite poems of hers that ooze with this tenderness are the ones to her fish Telly. As a baby poet I wouldn’t have dared to write about a dog, let alone a fish. To me, those were the type of silly poems white poets got to write because their world wasn’t under threat. But Toi taught me otherwise: that tenderness is as much my birthright, even if the world is determined to tell me otherwise.

Not only is Toi’s work a study on tenderness, but it is a model on the importance of the poetic line and line break, and the flexibility of language. When I read this poem, “Another poem of a small grieving for my fish Telly,” with my students, I remind them that we are to read both at the level of the sentence but also at the level of the line, so that we can hear the way Toi makes use of all the echoes or meanings behind a word or phrase.

From the very first line “Perhaps I should forgive” Toi gestures openly by breaking the line at forgiveness. So that, if you’ve read the rest of her book you can’t help but think she must be talking about her difficult father. Even reading the poem out of context, the line break leaves an openness that allows you to linger in the idea of forgiveness and the hesitancy of that “Perhaps” that starts the line. As a result, the reader enters the poem through the tension of forgiveness and recognizes that even if we are talking about “just/a fish” this will be a big poem.

Further, by repeatedly placing the “just” at the end of the line she emphasizes the word so that we hear the callousness of it. Just a tiny lesser being the speaker of those words seems to say just a tiny portion of your heart.

In the heart of this writer there is no “just.” Instead Toi instructs us that it is human to give the heart, not in portion, but wholly—even to something as tiny as a beta fish. Writing “when I poured Telly out/of his painted casked (a little wooden/egg) out over the rail/into the all/becoming, was it a miracle/ that he had lived, was it a miracle?” She asks us to stop and consider the destiny of the soul of this tiny being. My two favorite lines there are “into the all” and “becoming, was it a miracle.” When read at the level of the sentence the phrase is “into the all becoming,” which on its own feels like an appropriate description for the afterlife. However, by breaking it up, Toi allows us to sit in that “all” and, perhaps in doing so, shows us the connection between the soul of a fish and the soul of the human who cared for it. Some day we all, tiny or large being, will enter that all. Then in addition to the weighty expansiveness of that “all” we get the interesting question in the next line “becoming, was it a miracle,” which allows us to think about this conundrum of the soul more deeply. Isn’t it a miracle that we “become,” that we enter into existence at all?

Of course, being a poet, Toi leaves us with the question and leaps. In a line that sits alone at the center of a poem like a hinge, she begins the story of a time she prayed for a sign, and “God opened the closed.” This section of the poem has an ecstatic momentum to it that’s accentuated by the choices Toi makes when breaking her lines. For example, by breaking the line at “& hail, yes,” after describing the sky opening so the sun can shine directly on her face, Toi helps us hear an ecstatic “hell yes!” in that “hail, yes,” even without Toi directly putting those words in the poem. The ear can’t help but hear it and the line break accentuates that hearing.

Similarly, in the next stanza Toi manipulates the line in such a way that the meaning of the sentence is once again deliberately undermined or expanded. She writes “…I was/afraid to believe in love. God,/don’t waste your miracles on me. &/….” First by putting “God” at the end of the second line of that stanza the line becomes “afraid to believe in love. God” making it sound to the ear and eye that Toi is afraid to believe in both God and love. Or perhaps is afraid to believe more specifically in the “love God,” a fear which resonates with the physical and emotional violence we see in other portions of the book. Yet in the next line she writes “don’t waste your miracles on me. &” When I read these lines to my students I always point out that there was no reason that Toi had to put “God” at the end of the second line and “&” at the end of the third, except that she wanted us to push beyond the level of the sentence. And so that abrupt “&” at the end of “don’t waste your miracles on me,” quite immediately undermines the statement. It's as if she’s saying “don’t waste your miracles on me EXCEPT maybe do.” And I must say theres a vulnerability here that is so particular to Toi’s work. By undercutting these two sentences with her breaks, Toi shows a hesitation, an uneasiness with declaring a belief in love or God, a desire to throw off miracles and a desire for them. Theres a very human uncertainty that these choices bring out that is deeply relatable.

I used to rush to the end of this poem because of my excitement for the the final stanza “& father. Say it wasn’t my/fault you suffered…say you forgive me.” Here was the true heart breaking moment in the poem where the fish is revealed to be merely a vehicle for what I felt the poem must really be about: seeking forgiveness from the father, and that pervasive feeling of guilt that makes a child feel that they are the cause of their parents suffering. And to keep it for real, I still don’t think it's an accident that the final stanza starts “& father.” But I’ve come to realize, especially after re-reading this poem in the context of the other Telly poems, that to say the fish is only a vehicle would be a betrayal of the expansiveness of the heart of this poet. The fish leads to the father, not because of artifice or a false poetic craftiness, but because love leads you to love, and grief to grief. Of course the dead mother and father enter this poem about the dead fish because as she says in a later Telly poem:

“all things are

connected, a

circle,

bread on the water, as my mother said,

always comes home.”

(from “Because I was good to Telly in his life,")